Funny how things can pop into your head when you’re not thinking about them. I can’t remember why this occurred to me last week … but it was one of those thoughts I realized I should write down so I could use it later. So I tweeted it. Lots of people kindly “re-tweeted” the thought, which immediately made me self-conscious that it may not explain itself very well. So now I’m blogging about it. Because that’s what we kids do nowadays.

My tweet: User Experience Design is not data-driven, it’s insight-driven. Data is just raw material for insight.

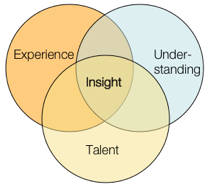

I whipped up a little model to illustrate the larger point: insight comes from a synthesis between talent, expertise, and the fresh understanding we gain through research. It’s a set of ingredients that, when added to our brains and allowed to stew, often over a meal or after a few good nights’ sleep, can bring a designer to those moments of clarity where a direction finally makes sense.

I’ve seen a lot of talk lately about how we shouldn’t be letting data drive our design decisions — that we’re designers, so we should be designing based on best practices, ideas, expertise, and even “taste.” (I have issues with the word “taste” as many people use it, but I don’t have a problem with the idea of “expert intuition” which is I think more what a lot of my colleagues mean. In fact, that Ira Glass video that made the rounds a few weeks ago on many tweets/blogs puts a better spin on the word “taste” as one’s aspiration that may be, for now, beyond one’s actual abilities, without work and practice.)

As for the word “data” — I’m referring to empirical data as well as the recorded results of something less numbers-based, like contextual research. Data is an input to our understanding, but nothing more. Data cannot tell us, directly, how to design anything.

But it’s also ludicrous to ask a client or employer to spend their money based solely on your expertise or … “taste.” Famous interior or clothing designers or architects can perhaps get away with this — because their names carry inherent value, whether their designs are actually useful or not. So far, User Experience design practitioners don’t have this (dubious) luxury. I would argue that we shouldn’t, otherwise we’re not paying much attention to “user experience” to begin with.

Data is valuable, useful, and often essential. Data can be an excellent input for design insight. I’d wager that you should have as much background data as you can get your hands on, unless you have a compelling reason to exclude it. In addition, our clients tend to speak the language of data, so we need to be able to translate our approach into that language.

It’s just that data doesn’t do the job alone. We still need to do the work of interpretation, which requires challenging our presuppositions, blind spots and various biases.

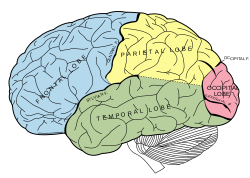

The propensity for the human brain to completely screw stuff up with cognitive bias is, alone, reason enough to put our design ideas through a bit of rigor. Reading through the oft-linked list of cognitive biases on Wikipedia is hopefully enough to caution any of us against the hubris of our own expertise. We need to do the work of seeing the design problem anew, with fresh understanding, putting our assumptions on the table and making sure they’re still viable. To me, at least, that’s a central tenet behind the cultural history of “user experience” design approaches.

But analysis paralysis can also be a serious problem; and data is only as good as its interpretation. Eventually, actual design has to happen. Otherwise you end up with a disjointed palimpsest, a Frankenstein’s Monster of point-of-pain fixes and market-tested features.

We have to be able to do both: use data to inform the fullest possible understanding of the behavior and context of potential users, as well as bring our own experience and talent to the challenge. And that’s hard to do, in the midst of managing client expectations, creating deliverables, and endless meetings and readouts. But who said it was easy?

I don’t have much to say about this, I just want to see if I can inject a meme in the bloodstream, so to speak.

I don’t have much to say about this, I just want to see if I can inject a meme in the bloodstream, so to speak.