This is based on a slide I’ve been slipping into decks for over a year now as a “quick aside” comment; but it’s been bugging me enough that I need to get it out into a real blog post. So here goes.

We hear the words Strategy and Innovation thrown around a lot, and often we hear them said together. “We need an innovation strategy.” Or perhaps “We need a more innovative strategy” which, of course, is a different animal. But I don’t hear people questioning much exactly what we mean when we say these things. It’s as if we all agree already on what we mean by strategy and innovation, and that they just fit together automatically.

There’s a problem with this assumption. The more I’ve learned about Communities of Practice, the more I’ve come to understand about how innovation happens. And I’ve come to the conclusion that strategy and innovation aren’t made of the same cloth.

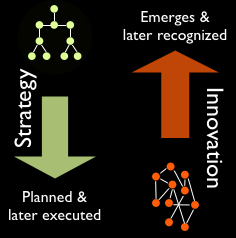

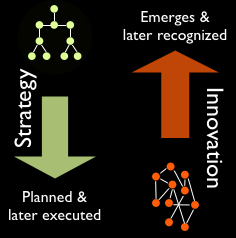

1. Strategy is top-down; Innovation is bottom-up

Strategy is a top-down approach. In every context I can think of, strategy is about someone at the top of a hierarchy planning what will happen, or what patterns will be invoked to respond to changes on the ground. Strategy is programmed, the way a computer is programmed. Strategy is authoritative and standardized.

Innovation is an emergent event; it happens when practitioners “on the ground” have worked on something enough to discover a new approach in the messy variety of practitioner effort and conversation. Innovation only happens when there is sufficient variety of thought and action; it works more like natural selection, which requires lots of mutation. Innovation is, by its nature, unorthodox.

2. Strategy is defined in advance; Innovation is recognized after the fact

While a strategy is defined ahead of time, nobody can seem to plan what an innovation will be. In fact, many (or most?) innovations are serendipitous accidents, or emerge from a side-project that wasn’t part of the top-down-defined work load to begin with. This is because the string of events that led to the innovation is never truly a rational, logical or linear process. In fact, we don’t even recognize the result as an innovation until after it’s already happened, because whether something is an innovation or not depends on its usefulness after it’s been experienced in context.

We fill in the narrative afterwards — looking back on what happened, we create a story that explains it for us, because our brains need patterns and stories to make sense of things. We “reify” the outcome and assume there’s a process behind it that can be repeated. (Just think of Hollywood, and how it tries to reproduce the success of surprise-hit films that nobody thought would succeed until they became successful.) I discuss this more in a post here.

3. Strategy plans for success in known circumstances; Innovation emerges from failure in unknown circumstances.

One explicit aim of a strategy is to plan ahead of time to limit the chance of failure. Strategy is great for things that have to be carried out with great precision according to known circumstances, or at least predicted circumstances. Of course strategy is more complex than just paint-by-numbers, but a full-fledged strategy has to have all predictable circumstances accounted for with the equivalent of if-then-else statements. Otherwise, it would be a half-baked strategy. In addition, strategy usually aims for the highest level of efficiency, because carrying something off with the least amount of friction and “wasted” energy often makes the difference between winning and losing.

However, if you dig underneath the veneer of the story behind most innovations, you find that there was trial and error going on behind the scenes, and lots of variety happening before the (often accidental) eureka moment. And even after that eureka moment, the only reason we think of the outcome as an innovation is because it found traction and really worked. For every product or idea that worked, there were many that didn’t. Innovation sprouts from the messy, trial-and-error efforts of practitioners in the trenches. Bell Labs, Xerox PARC and other legendary fonts of innovation were crucibles of this dynamic: whether by design or accident, they had the right conditions for letting their people try and fail often enough and quickly enough to stumble upon the great stuff. And there are few things less efficient than trial and error; innovation, or the activity that results in innovation, is inherently inefficient.

So Innovation and Strategy are incompatible?

Does this mean that all managers can do is cross their fingers and hope innovation happens? No. What it does mean is that to having an innovation strategy has nothing to do with planning or strategizing the innovation itself. To misappropriate a quotation from Ecclesiastes, such efforts are all in vain and like “striving after wind.”

Managing for innovation requires a more oblique approach, one which works more directly on creating the right conditions for innovation to occur. And that means setting up mechanisms where practitioners can thrive as a community of practice, and where they can try and fail often enough and quickly enough that great stuff emerges. It also means setting up mechanisms that allow the right people to recognize which outcomes have the best chance of being successes — and therefore, end up being truly innovative.

I’m as tired of hearing about Apple as anyone, but when discussing innovation they always come up. We tend to think of Apple as linear, controlled and very top-down. The popular imagination seems to buy into a mythic understanding of Apple — that Steve Jobs has some kind of preternatural design compass embedded in his brain stem.

Why? Because Jobs treats Apple like theater, and keeps all the messiness behind the curtain. This is one reason why Apple’s legal team is so zealous about tracking down leaks. For people to see the trial and error that happens inside the walls would not only threaten Apple’s intellectual property, it would sully its image. But inside Apple, the strategy for innovation demands that design ideas to be generated in multitudes like fish eggs, because they’re all run through a sort of artificial natural-selection mechanism that kills off the weak and only lets the strongest ideas rise to the top. (See the Business Week article describing Apple’s “10 to 3 to 1” approach. )

Google does the same thing, but they turn the theater part inside-out. They do a modicum of concept-vetting inside the walls, but as soon as possible they push new ideas out into the marketplace (their “Labs” area) and leverage the collective interest and energy of their user base to determine if the idea will work or not, or how it should be refined. (See accounts of this philosophy in a recent Fast Company article.) People don’t mind using something at Google that seems to be only half-successful as a design, because they know it’ll be tweaked and matured quickly. Part of the payoff of using a Google product is the fun of seeing it improved under your very fingertips.

One thing I wonder: to what extent do any of these places treat “strategy” as another design problem to be worked out in the bottom-up, emergent way that they generate their products? I haven’t run across anything that describes such an approach.

At any rate, it’s possible to have an innovation strategy. It’s just that the innovation and the strategy work from different corners of the room. Strategy sets the right conditions, oversees and cultivates the organic mass of activity happening on the floor. It enables, facilitates, and strives to recognize which ideas might fit the market best — or strives to find low-impact ways for ideas to fail in the marketplace in order to winnow down to the ones that succeed. And it’s those ideas that we look back upon and think … wow, that’s innovation.

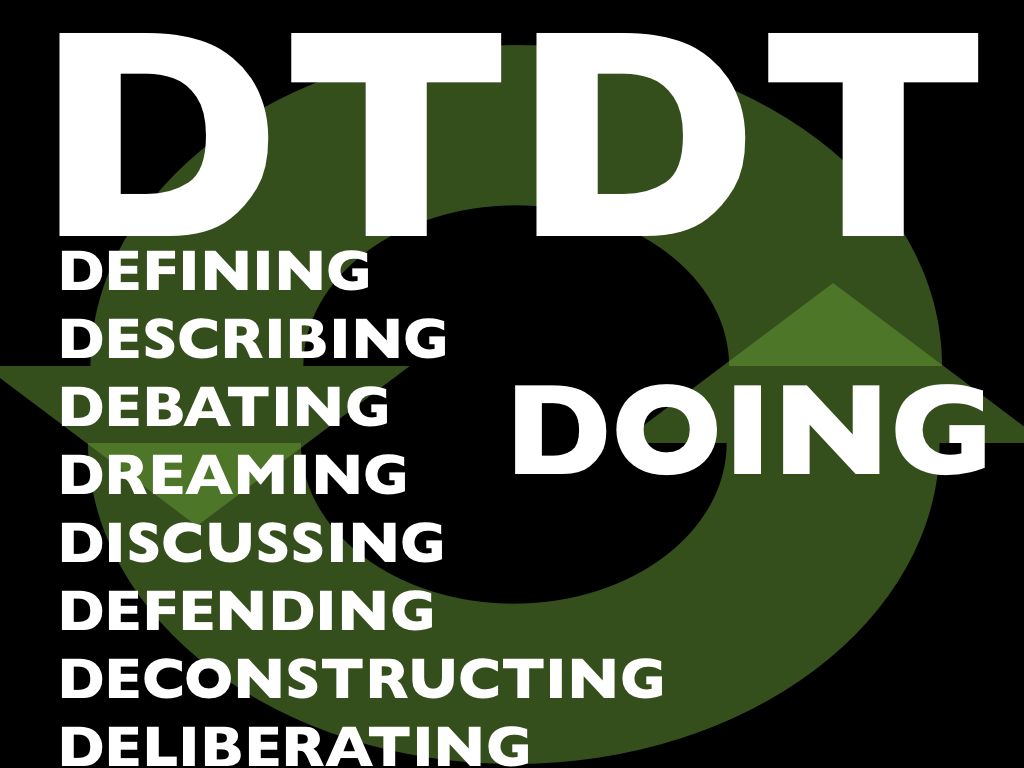

I don’t have much to say about this, I just want to see if I can inject a meme in the bloodstream, so to speak.

I don’t have much to say about this, I just want to see if I can inject a meme in the bloodstream, so to speak.